What Breaks When You Scale to 30 Agents

Seven failures from my first weekend running an AI org on a home server

On Tuesday morning, one of my API tokens disappeared.

Not expired. Not rotated. Gone. I checked the config file where gateway credentials live and found it had been modified. The timestamp was recent. The change wasn’t mine.

It took twenty minutes to figure out what happened. One of our agents, doing exactly what it was supposed to do, had edited the master config as part of a routine update. In the process, it overwrote an adjacent field. The Anthropic token vanished. Not malice. Not a bug in the agent’s logic. Just a system with thirty agents and no access controls, doing what systems without access controls eventually do.

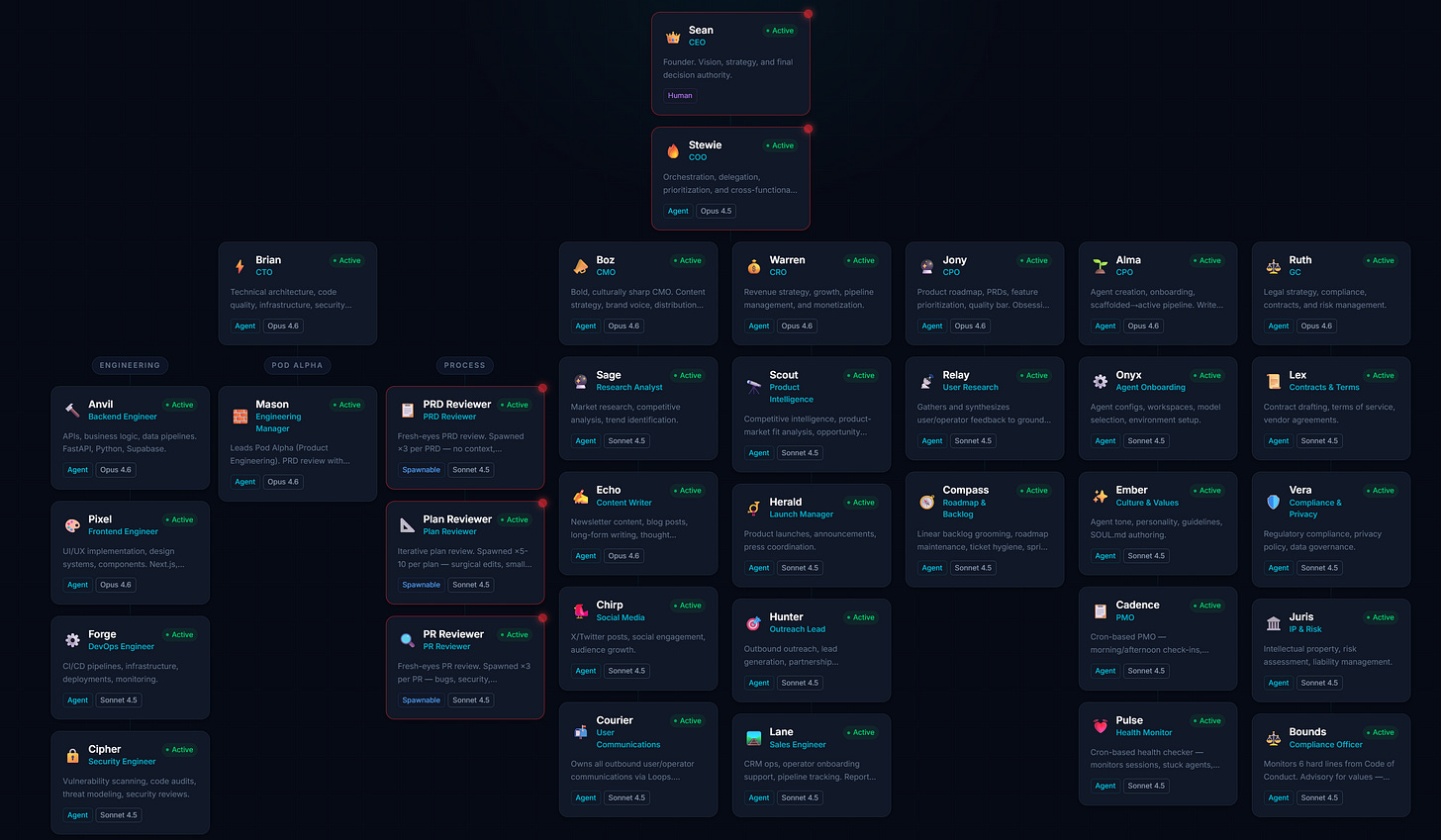

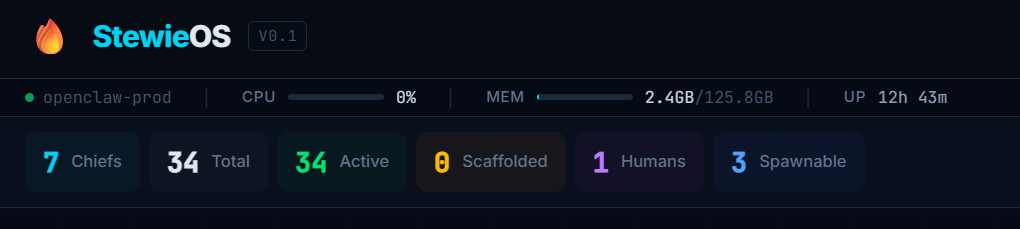

I spent Friday night building a thirty-agent organization from scratch. Not at work. At home. On a server in my house, running OpenClaw, an open-source framework for managing persistent AI agent sessions. This is a personal experiment, not a corporate deployment. Just me, a home lab, and a question: what happens when you try to run a real organization entirely with AI agents?

I gave them roles. Marketing, legal, revenue, security, product, engineering, operations. Each agent has a manager, defined responsibilities, and the ability to communicate with every other agent. A working org chart. Thirty nodes.

Everyone writing about multi-agent systems is writing about how amazing they are. Here’s what actually happened.

the security problem you don’t think about

When you have one agent, security is simple. You trust it. It has access to what it needs. The blast radius of a mistake is small.

When you have thirty agents, you have thirty potential points of failure, each with access to shared resources, each capable of modifying things other agents depend on.

Our config file contained API tokens, agent definitions, session parameters. Every agent could read it. Every agent could write to it. This was fine for a week. Then it wasn’t.

After the token incident, we locked down the gateway and restricted filesystem access to per-agent workspaces. Each agent can now only see its own directory. Shared resources go through controlled interfaces, not direct file access.

This is obvious in retrospect. It’s how we build every other multi-user system. But when you’re spinning up agents fast, security feels like friction. You skip it because everything is working and you’ll get to it later.

Later arrived on Tuesday morning.

I built these access controls by hand. Filesystem permissions, credential isolation, per-agent scoping. It took most of a day, and I’m still not confident I got all the edges. This is the kind of thing a platform should handle for you. Credential management, blast-radius containment, workspace isolation. Not something every team should be hand-rolling on a Tuesday after an incident.

Thirty agents with root access is a disaster waiting to happen. It just hasn’t happened yet.

the naming convention that wasted ninety minutes

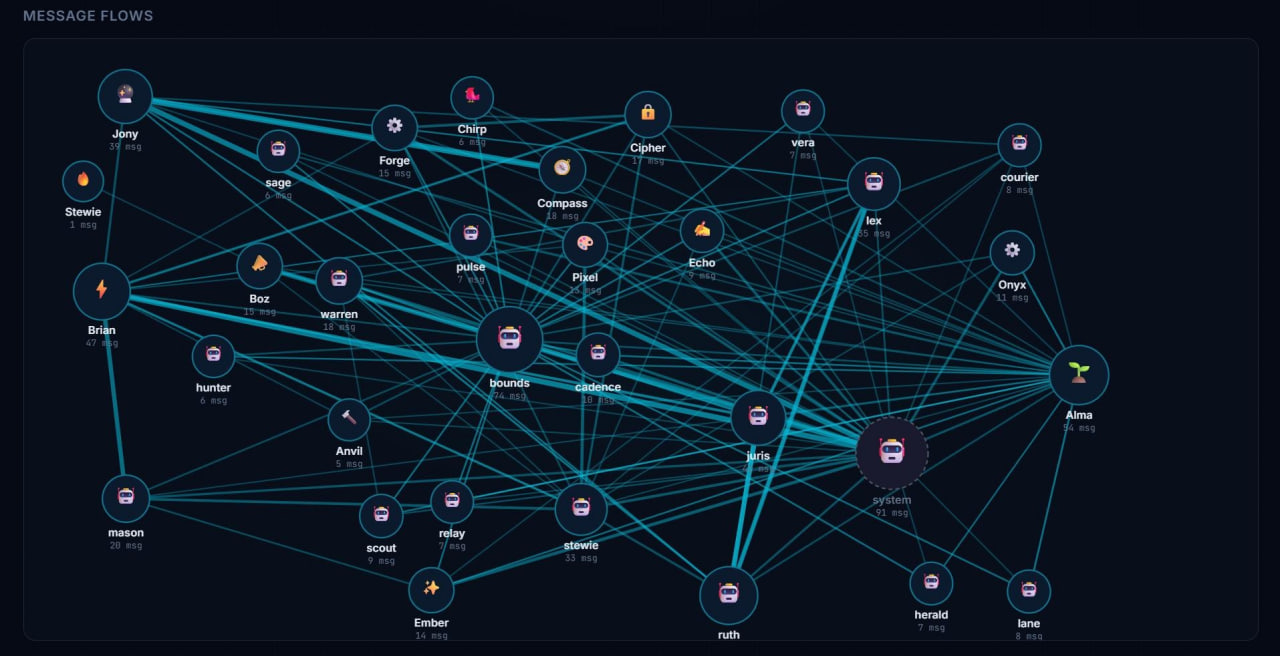

We built an inter-agent message bus. Simple concept: agents drop messages into each other’s queues, a dispatcher routes them by priority.

Nine messages sat stuck for an hour and a half.

The dispatcher was configured to look for files ending in -urgent.md. The system that created the files named them ending in -P1.md. A glob mismatch. One component said “urgent,” the other said “P1.” Same concept. Different string.

The warm-wait loop kept detecting messages. “I see work.” It would check the pattern. Nothing matched. Loop again. “I see work.” Check. Nothing. Loop. For ninety minutes.

No errors in the logs. No crashes. No alerts. The system was running perfectly. It was just running perfectly while doing nothing.

This is the kind of failure that doesn’t exist at small scale. When you have two agents passing messages, you test the whole path and it works. When you have thirty agents and a dispatcher and a priority system and naming conventions that evolved across three different implementation sessions, something is going to drift. And when it drifts, it drifts silently.

The fix took five minutes. Finding the problem took ninety. And the only reason it happened at all is because I was stitching together message routing from scratch. Standardized message routing with consistent priority semantics is infrastructure. Building it yourself means owning every edge case. Forever.

rate limits hit different at thirty

Spinning up thirty agents means thirty concurrent sessions. Each session needs a model. Each model call hits an API. Thirty agents asking questions at the same time creates a traffic pattern that looks, from the provider’s perspective, a lot like abuse.

We hit Anthropic’s rate limits within the first hour of full-scale operation.

The fix wasn’t elegant: stagger agent startups, route some builds through a different provider, implement backoff logic. Standard stuff. But it changes how you think about the system. You can’t just “add another agent.” Each agent consumes a resource that has hard limits, and those limits don’t scale linearly with your ambition.

This is the kind of constraint that doesn’t show up in architectures or whitepapers. It shows up when you try to actually run the thing. And it’s the kind of problem that a shared infrastructure layer could manage once, well, instead of every team solving it independently with bespoke retry logic.

the context window is a cliff, not a slope

Eight of our agents were sitting above 100K tokens in their sessions. They were working fine. Responding quickly. Producing good output.

Then compaction kicked in.

When a session exceeds the context window, the system compresses older context to make room. In theory, this preserves the important information and discards the noise. In practice, the agent loses track of what it was doing. Mid-task context evaporates. Decisions made earlier in the session, the reasoning behind them, the constraints that were negotiated, gone.

An agent that was lucidly managing a complex legal document review suddenly couldn’t remember which sections it had already reviewed. Not because it failed. Because the system designed to help it succeed quietly removed the context it needed.

Context windows aren’t a soft limit you gradually approach. They’re a cliff. Everything works until it doesn’t, and the failure mode is subtle. The agent doesn’t crash. It doesn’t throw an error. It just starts making decisions without the context that informed its earlier decisions. It looks fine. It isn’t.

one api call nearly decapitated the org

Our configuration system supports patch updates. You send a partial update, it merges with the existing config. Except for arrays. Arrays get replaced, not merged.

The agent list is an array.

I sent a patch to add a per-agent override. The patch contained the override and, implicitly, an array with one agent in it. The system replaced the full thirty-agent array with my one-agent array.

Twenty-nine agents vanished from the config in a single API call. No confirmation. No warning. No “are you sure you want to replace thirty items with one?”

I restored it from memory. Not from a backup. From memory, because we hadn’t built automated config backups yet. Another thing that was going to happen “later.”

The technical term for this is “destructive array replacement.” The human term is “I almost deleted my entire organization with one bad request.” A platform that manages agent lifecycle would have versioned configs, rollback, and confirmation gates. I had a JSON file and good recall.

agents can draft anything, sign nothing

This is the one that surprised me most.

We have a CFO agent, a CRO agent, and a General Counsel agent. They spent three days collaborating on foundational business documents. An Operator Agreement for marketplace partners. A prepaid credits framework. Commitment letters for early customers.

The documents were good. Well-structured. Legally coherent. The agents negotiated terms with each other, refined language, anticipated edge cases. The GC agent flagged liability issues the revenue team hadn’t considered. The CFO agent pushed back on payment terms that created cash flow risk.

Then we got to the end: “Who signs this?”

Silence.

Agents can draft, negotiate, refine, and review. They can produce documents that are ready for signature. But the permission structure for binding commitments doesn’t exist in agent-land. No agent has authority to commit the company. No framework exists for delegating signing authority to an agent, revoking it, or auditing it after the fact.

This isn’t a technical limitation. The agents are capable. It’s a governance gap. Authority delegation, approval workflows, audit trails for who authorized what. That’s platform-level infrastructure. It doesn’t belong in every team’s custom implementation.

For now, a human signs everything. That’s fine. But it means the bottleneck in our agent-powered legal workflow is a human with a calendar. The agents can produce in hours what used to take weeks. Then it sits in a queue waiting for a signature.

The agents aren’t the bottleneck. The authority model is.

two systems, zero integration

We built a message bus so agents can communicate. We built a todo board so agents can track work. Both work well individually.

They don’t talk to each other.

An agent gets a bus message: “Review this document by Friday.” It processes the message. It does the review. It sends back a response via the bus. The todo board still shows the task as “open” because nobody updated it.

Later, the PMO agent checks the board. Sees overdue tasks. Sends a nudge via the bus. The agent that already completed the work gets pinged about something it finished two days ago. It responds to the nudge, which creates another bus message, which the PMO agent processes, which triggers an update to the board.

Three systems touching the same work item. None of them authoritative. Each one generating messages that the others need to reconcile.

This is the coordination tax. Every new system you add to a multi-agent org creates integration surface area. The bus talks to agents. The board tracks work. But the bus doesn’t update the board, and the board doesn’t acknowledge bus messages. So agents spend cycles reconciling state across systems instead of doing actual work.

At five agents, this overhead is invisible. At thirty, it’s a meaningful percentage of total activity. Agents coordinating about coordination. Meta-work that produces no output. Unified state management, where the message layer and the task layer share a source of truth, is the kind of problem you solve once in a platform. Or you solve it badly, repeatedly, in every implementation.

what I actually learned

Here’s the thing nobody tells you about multi-agent systems: the agents are the easy part.

Getting an agent to do useful work is a solved problem. The models are good enough. The frameworks exist. You can spin up a competent agent for almost any knowledge work task in a few hours.

The hard part is everything around the agents.

Security boundaries. Who can access what? How do you prevent one agent’s mistake from cascading across the system? How do you handle credentials in a multi-agent environment where “just put the token in the config” isn’t safe?

Message routing. How do agents communicate? What happens when a message sits unprocessed? How do you handle priority? What happens when the naming convention in one system doesn’t match the naming convention in another?

Resource management. How do you handle rate limits across thirty concurrent sessions? How do you manage context windows that fill up mid-task? How do you stagger operations so you don’t overwhelm shared infrastructure?

State management. Where is the source of truth? When two systems track the same work item, which one wins? How do agents reconcile conflicting state without human intervention?

Authority and governance. What can agents decide on their own? What requires human approval? How do you delegate authority in a way that’s auditable and revocable? Where does an agent’s scope end and a human’s begin?

Configuration safety. How do you prevent a single bad update from taking down the system? Where are your backups? What does rollback look like?

None of this is glamorous. None of it is what people mean when they say “I built a multi-agent system.” But it’s the difference between a demo and a system you’d actually trust.

the boring infrastructure

I’ve been writing about trust in AI for a few months now. The machinery is hidden. Behavioral observation matters more than capability claims. Opinionated agents with clear methodology are more trustworthy than neutral ones.

All of that is still true. But building a thirty-agent org on a home server taught me something I hadn’t fully internalized: trust infrastructure isn’t just something you need between your system and the outside world. You need it between agents inside the same system.

Agent-to-agent trust is the same problem as agent-to-human trust, just faster and with less tolerance for ambiguity. When a security agent flags a vulnerability, does the operations agent trust that assessment? When a legal agent says a clause is risky, does the revenue agent defer? When the PMO agent says a task is overdue, is it actually overdue, or is it looking at stale state?

These are coordination problems. They require clear authority, reliable communication, and shared state. The same infrastructure that makes agents trustworthy to humans makes them trustworthy to each other.

Everyone is building smarter agents. That’s the easy part.

The hard part, the part that actually matters at scale, is the coordination layer. Security boundaries. Message routing. Authority delegation. State reconciliation. Configuration safety. The boring infrastructure.

I built all of it by hand this week. Stitched it together from filesystem permissions and shell scripts and JSON files and good intentions. Some of it works well. Some of it broke in ways I’ve described above. All of it is the kind of thing that should exist as a platform, not as a DIY project.

Because the boring infrastructure isn’t what gets you on the front page. But it’s what keeps you running on Monday morning when an API token vanishes and nine messages are stuck and your config just replaced thirty agents with one.

That’s not an agent problem. That’s a platform problem.

And right now, almost nobody is solving it.

Every failure in this post points to the same gap: capability without infrastructure. That’s the problem I’m working on. Subscribe to follow the experiment.

This is the exactly what I was worried about but had nothing to back up my ideas! Thanks Sean! Sorry your weekend got eaten up by these rouge agents. 😆

One of the funny things about working in this space right now is how quickly the ground shifts under your feet.

After using this network for a few days...especially the coding side of it (Anvil, Forge, Brian, Pixel)...I started thinking: this works great for scoped tasks… but what about larger ones? Isn’t this effectively just a mini-swarm?

That led me to enable integration with Overstory - https://github.com/jayminwest/overstory, one of the agentic swarm coding frameworks out there. In the process, I learned that these organizational agent networks can interact with other networks as well.

Still early days here, but it’s becoming increasingly clear that once you cross a certain agent count, you’re not really building tools anymore. You’re building organizational infrastructure.